In a recent Citizen One essay, I wrote about an ancient strangler fig tree I encountered high atop the old Kasbah in Tangier, Morocco—how its roots consumed colonial ruins and stitched time into the city around it. That wasn’t just a meditation on urban landscape. It was an argument: that trees are not scenery; they’re structures, if not cathedrals, of cities and towns. They are often keepers of what cities so often forget.

From North Africa to the American Gulf Coast of Mexico, these rooted sentinels carry more than chlorophyll; they carry memory, resistance, shelter, grief, and transformation. This next essay continues that conversation beneath another tree—the Ruskin Oak of Ocean Springs, Mississippi—where a different kind of counter-history unfolds, one shaped not by empire, but by artists, potters, and the quiet defiance of remaining distinctly human.

The Ruskin Oak stands near the curve of Ruskin Avenue, just south of Cleveland and west of the bluff where Ocean Springs lets out its last sigh before reaching the Gulf shoreline. This live oak sprawls across the earth like a sleeping leviathan amidst a quiet neighborhood that’s seen more floods than mercy. Its limbs don’t just bend—they slam into the soil and rise again, as if the tree is wrestling the ground into remembering. It’s survived more hurricanes than FEMA, FEMA’s predecessor, and whatever deity used to handle storm logistics before that. The branches twist and lurch with the weight of memory, shaped by centuries of wind, salt, and Southern silence. The air smells of brine, clay, and something older still.

The Ruskin Oak, named for the 19th-century English critic John Ruskin (1819–1900), became a spiritual totem for the Andersons. Ruskin was a British art critic and social thinker who championed craftsmanship, nature, and moral imagination. He warned that industrialization was stripping meaning from labor and beauty from everyday life. His writings inspired the Arts and Crafts movement and communities like Shearwater Pottery. Naming a centuries-old oak after him must have just felt right, as Ruskin believed in things shaped with care, rooted in place, and built to last.

The Ruskin Oak is at least 350 to 400 years old, perhaps older—a living witness to the layered, contradictory story of the Gulf Coast. The kind of tree that survives by listening—to weather, to silence, and to time.

The Anderson’s, a local family of artisans, transformed that oak tree into their compass.

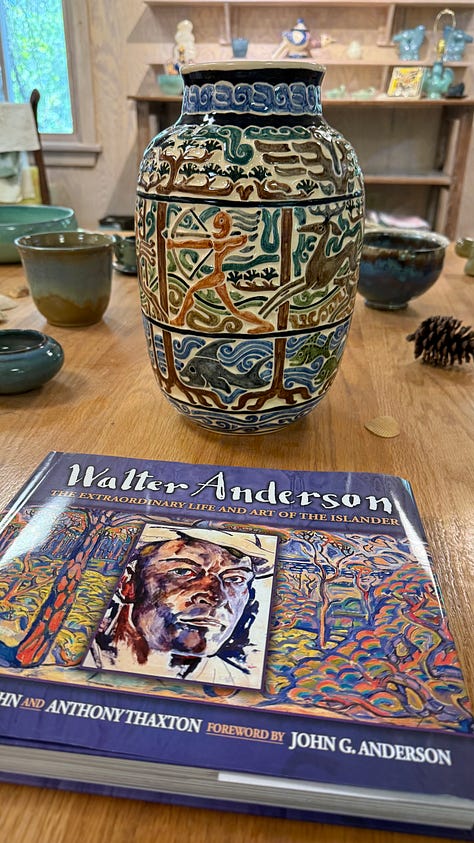

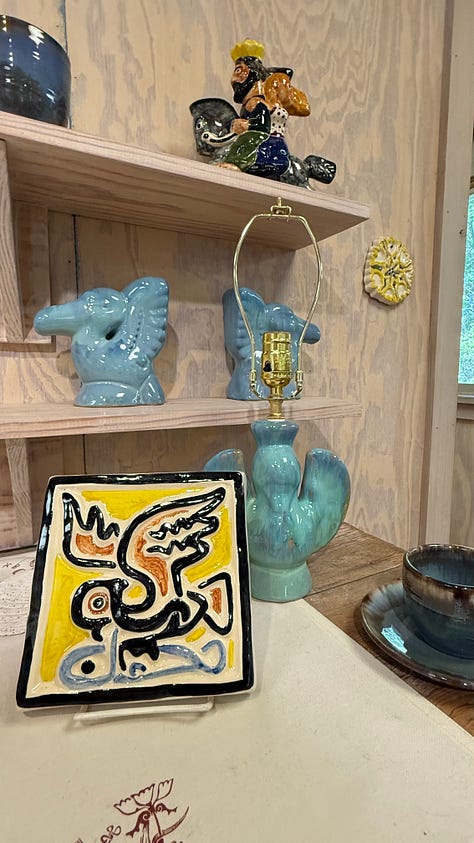

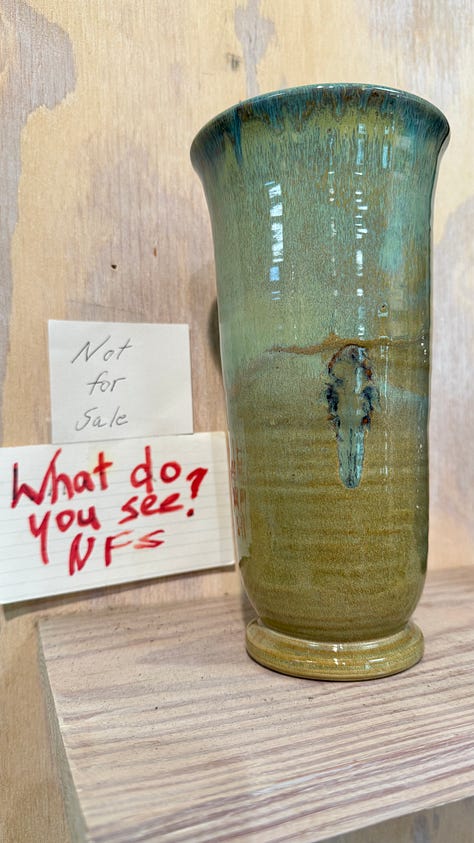

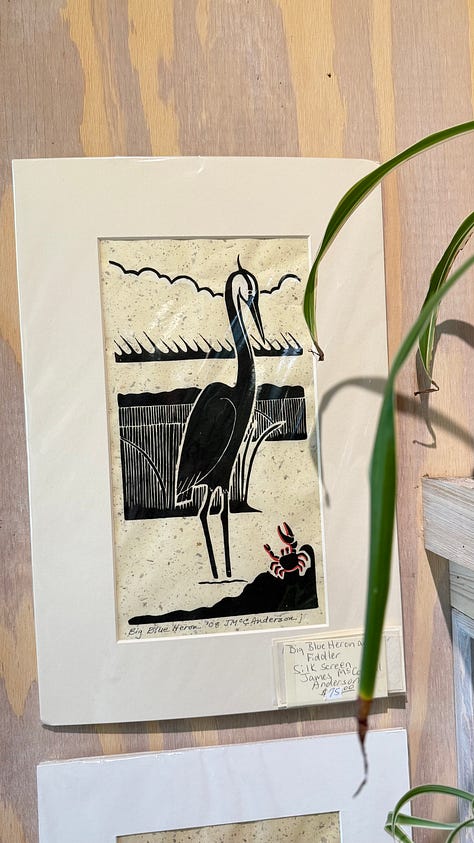

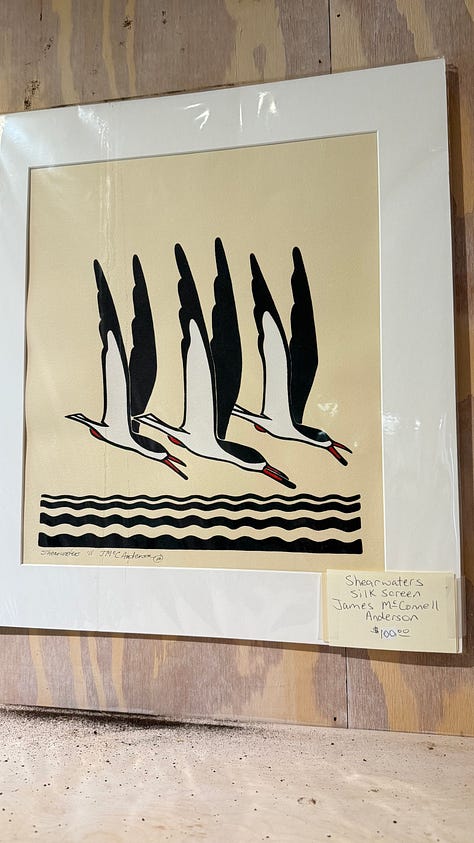

Nearby Shearwater Pottery began in 1928, when Peter Anderson, the eldest of three brothers, built a small studio tucked inside the wooded expanse of other live oak woods of Ocean Springs. Peter had studied ceramics in New York, but the family’s vision was always rooted in the land. His brother Walter Anderson, a mystic painter and naturalist, soon turned the studio into a living laboratory of color and myth. His murals and painted pottery became emblematic of a deep Southern animism—crabs rendered like deities, birds mid-flight with their wings bent in prayer. Their brother Mac sculpted mythic creatures. Together, they shaped clay into an American counter-modernism.

The Anderson’s never used the word innovation. They didn’t need to. By refusing mass production, embracing human imperfection, and collapsing the boundaries between utility and spirit, this family, deeply rooted in the early American Arts and Crafts movement, seeded one of the most enduring experiments in artist-led, anti-industrial creativity in the United States. Their work was—and still is—both artifact and argument.

But the ground they stood on held much older stories.

Ocean Springs was first known to the Biloxi people, a Native American group who lived across the coast and its inland waterways. They fished the marshes, harvested oysters, and shaped the culture of the region long before the French arrived. In 1699, the French established Fort Maurepas nearby, claiming it as part of La Louisiane. Ocean Springs became one of the first colonial settlements on the Gulf Coast. Later came the Spanish, shifting control and influence across the 18th century before it came under American control in the 1800s. But beneath every layer—Native, French, Spanish, Confederate, American—these live oaks endured.

Before the French planted flags or drew borders on stolen paper, this coast belonged to the Biloxi—a Siouan-speaking people whose stories didn’t fit easily into the neat boxes of colonial record-keeping. They lived in kin-based communities along the bay and barrier islands, harvesting oysters, planting maize, and pulling redfish from the marsh with a fluency no empire could ever teach. Their language, long since extinguished, was an anomaly—an outlier in the linguistic quilt of the Southeast, whispered through trees older than any cathedral in Europe.

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville (1661–1706) was a French-Canadian naval officer, explorer, and colonizer who led France’s first successful expedition to establish a permanent settlement here on the Gulf Coast. In 1699, he founded Fort Maurepas near present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi, in the shadow of a Biloxi village. The Biloxi traded, observed, endured. Then came the slow violence—disease, migration, erasure. By the late 1700s, the tribe had fractured and moved west, eventually merging with the Tunica, surviving in name if not in geography. Their footprints may not appear on the “original” blueprints of Ocean Springs, but they’re there nonetheless—pressed into the soil, layered beneath every fired pot, painted heron, and kiln-fired, artisanal masterpiece that followed.

We speak of Gulf Coast art like it emerged like a new-born baby into the wilderness, as if this natural coastal expanse was some blank canvas. It wasn’t. It was a world already made—human, old, complex. The Andersons inherited that silence, even if they didn’t always name it.

Ruskin often warned against the deadening effects of industrialization, calling for art rooted in nature, made by hand, and animated by moral imagination. The oak embodied all of that. It shaded the pottery compound. It watched over the firing of kilns. It became a fixed point of resistance—a reminder that not everything had to be measured, monetized, or engineered into submission.

After exploring the Shearwater Pottery enclave recently, I keep returning to that image—especially now, as we watch AI systems mimic the human voice, concrete swallow the last wild acres of the Global South, and a thousand “smart city” brochures pitch us algorithmic futures nobody asked for.

Two years ago, I sat across from acclaimed architect Jean Nouvel in his atelier in Paris to discuss the future of cities. He demonstrated the same theatrical calm he brings to urban spaces—deliberate, sensory, and designed. We talked not about towers or steel, but about memory, absence, and the violence of homogeneity, and of the need for artists and poets to be allowed to become the sculptors of the city of the future. Of how the city must remain a human emotion.

I remember nodding. But what I should’ve said was: the city must also become a poem.

We’ve been sold a lie—that innovation means speed, scale, and compliance. But innovation, when it matters, is not born in labs or spreadsheets. It begins in the crawlspace between memory and imagination. It begins beneath trees like the Ruskin Oak, in places where the world is not designed to be consumed, but interpreted.

The Andersons didn’t set out to change the world. They just made pottery in a compound hidden among the live oak trees. But what they did—in their refusal to standardize, in their commitment to clay, in their defiance of industrial ease—was innovation. Not capital-I Innovation, the kind with PowerPoint slide decks or TED Talk stages, but the real kind. The kind that grows slowly, changes you, and sticks to you like grits.

Even during the Great Depression, Shearwater endured. Even after Hurricane Camille in 1969—and again after Katrina in 2005, which nearly wiped them out—they rebuilt. Walter Anderson, long gone by then, had already become myth. A man who once paddled a tiny skiff 12 miles to uninhabited Horn Island to paint egrets and sun gods. Who covered the walls of his cottage with mythological murals that no one saw until after his death. Who left behind notebooks filled with constellations, birds, and cryptic fragments that seemed to reach for some cosmic grammar of being.

Today, the Anderson family still runs Shearwater. Walter’s descendants fire kilns in the same grove of live oak trees. His murals hang in the Walter Anderson Museum of Art, and the Ruskin Oak still stands, heavy with history and lichen.

Today, we face a crisis of imagination—not because we lack tools, but because we lack enough truthful spaces. We’ve built cities and towns around rivers of capital instead of creative streams. We’ve erased the atelier and the pottery studio and replaced it with the Amazon logistics warehouse. We’ve forgotten that human complexity—the messy, the handmade, the unresolved—is not a design flaw. It’s a blueprint.

Whether we’re navigating the design and engineering complexities of the mirrored vastness of NEOM’s Line, rising from the Saudi desert or walking the high-altitude edge of Alatau’s smart city in Kazakhstan’s vast plateaus, the ambition remains the same: to conjure a new kind of civic language. These emerging smart cities promise algorithmic precision, climate resilience, and engineered elegance. But small, climate-resilient coastal towns like Ocean Springs, with its salt air and lichen-covered history, remind us of something subtler: that cities and towns are not made by code or concrete alone—they are made by people who remember how to belong to each other. And here’s the truth: no matter the altitude or latitude, whether carved into desert mountain tops or coastal marshes, every city—new or old—needs the same thing. A shared humanity. Without that, even the most dazzling metropolis becomes sterile. With it, even the smallest village can carry the weight of the future.

Acclaimed potters like Walter Anderson understood that. So did naturalists like Ruskin. So does Jean Nouvel, whose buildings still try to breathe in defiance of flat-packed, shrink-wrapped global architecture. They remind us: there is no urban innovation without the soul of poets and artists.

If we are to build resilient cities and towns that survive what’s next—climate collapse, automation, and the slow erosion of meaning—we have to return to that place. To the grove of live oaks. To the studio. To the page. To the poem.

The next urban revolution won’t be built solely by consultants with KPIs or performance dashboards. It will be seeded by artists and poets, by those stubborn enough to insist that a city must still ache, still sing, still hold contradictions. It will be shaped by hands in wet clay, by brushstrokes, by song, by story.

It will grow slowly. Like an oak.